This week we have a special feature: an interview with the author. Theresa Kishkan is both a writer and a sewist, and has shared some of both of those worlds with us. Read on for more! |

| photo credit Alexandra Bolduc

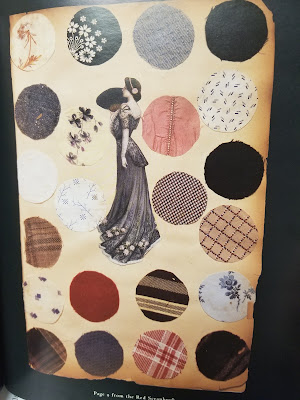

|

1. Welcome, Theresa, and thank you for taking the time to do this interview for the Literary Sewing Circle! Can you tell us a bit about how you came to write Sisters of Grass? What was the genesis of this story?

It’s a pleasure to answer these questions, Melanie. When my children were young, we camped in the Nicola Valley every summer and explored it widely. It interested me in so many ways. The Indigenous and settler histories are entwined, the ecosystem is very lovely, and its social context seemed almost like a microcosm of so much of what our society was grappling with: land use and values, reconciling histories, and so on. I remember driving up onto the Douglas Plateau one October with a picnic and feeling the extraordinary sense of the present and past existing in a series of layers. A truck filled with fly-fishers on their way to the old lodge on Pennask Lake passed us, dust rising from the truck’s wheels while an Indigenous man repaired fences. As I was thinking this, a little herd of horses, turned out after the cattle had all been brought down to their winter quarters, approached us and one of them, a bay mare, came right up to me as though we’d known each other all our lives. The moment shimmered (I can only describe it that way). And in my attempt to write a poem about it, because in those years, I was a poet, I realized I’d need more time, more space (both imaginative and actual; I needed pages...) to write about where the encounter with the lovely horse was taking me. I hadn’t written a novel before and learned as I went along how to shape the narrative, organize elements of plot and so on, but I felt I was so deeply immersed in the place itself that I really just needed to pay attention. I wanted to know what it might have been like to grow up in that area at a time before my own and writing my way into the story was the best way to do this.

2. There is a theme of material history through textiles in this book, as Anna, our modern-day curator, imagines the life of Margaret Stuart a century before. Was museum work something you had training in yourself, or was this interest due to your own experiences with textiles?

I have no training in either museum work or in the conservation of textiles but I’ve always been drawn to women’s textile work and how it is often a way of encoding and preserving history. (I hadn’t yet read Elizabeth Wayland Barber’s Women’s Work: The First 20000 Years but when I did find that book, I realized I was on the right path.) We spent time in the Four Corners area of the US when my husband was a visiting poet at a university there and we visited lots of Indigenous museums with displays of sandals woven of yucca fibre, beadwork, medicine bags beautifully decorated with quills, as well as community museums with the exhibits of a settler past; I loved the samplers, the quilts, the clothing, and the homely objects such as tea towels, often embellished, and tablecloths, etc. I realized that such work is almost subversive, practical and necessary, but also so satisfying to create, communally or individually. It’s a way of passing along knowledge and information.

My daughter, a child when I wrote Sisters of Grass, is a collections manager in a large museum, a position she arrived at circuitously. She was a graduate student in classical studies and worked part-time at a heritage site that had been damaged in a fire. She learned conservation skills and eventually took courses in museum studies and arrived at her current job that way. In many ways she has my alternate life, living in the city where I was raised, working at a museum I’ve always known, and when I visit her, I love spending time in the collections, looking at fragments of early baskets, textiles, and other evidence of women’s work as part of our foundational history.

I did work for a few hours a week in the Special Collections department at the University of Victoria’s main library when I was an undergraduate student and I remember how exciting it was when a box of materials came from one of the writers whose papers the department collected – Robert Graves, John Betjeman, a few others. These weren’t textiles of course but the materials were eclectic – everything from drafts of poems to shopping lists and correspondence – and often I’d be asked to do a preliminary sorting. I know that Anna would have felt a similar excitement as she gathered materials for her exhibit and I took the opportunity to embed some objects owned by myself or friends into her curatorial findings.

3. The setting of the Nicola Valley is a character in itself in this book. I feel like all your earlier poetry and essays come through in its really beautiful evocation. Do you have any strong feelings about place in forming a person's identity?

I do think we are profoundly shaped by place in ways we understand and also in mysterious ways. I wrote Sisters of Grass in some respects to imagine what it would have been like to have been born in that landscape, in that intersection of history and culture, to have attended services in the Murray Church in the little town of Nicola itself, to have walked through its tiny graveyard and read the names of the dead on the weathered stones and wooden crosses, names that still echo in the valley: the Coutlees, the Lauders, the Guichons. In the most self-serving of ways, writing the novel was an excuse for me to go regularly to the Nicola Valley to visit the archives or to ride in the hills or simply sit on the shores of Nicola Lake with the remnants of kikuli houses around me and dream my way back.

4. Margaret's mother is Indigenous and Margaret has a strong relationship with her grandmother, learning traditional skills based in the landscape. Her character reveals two strands of life in the Valley. Why was it important to you to show both in this particular way?

From my first visit to the Nicola Valley, I began to understand that the Indigenous and settler histories are entwined. The Indigenous history is much older; though the settler history is the one you see as you enter the valley, passing old worn barns, cabins, the gracious hotel at Quilchena, built in anticipation of a railway that was never built. You pass through the Spahomin reserve enroute to the Douglas Lake Ranch, the Lower Nicola reserve if you drive from Spences Bridge to Merritt along a highway that has since been mostly washed away from the atmospheric river weather event of 2021. Higher on hills above the Coldwater River, the Coldwater band has had a village site for thousands of years. In the archival record, Indigenous and settler names show up on school lists, results of horse races, accounts of cattle drives, marriages, and so on. Reading between the lines in books such as Jean Barman’s Sojourning Sisters: The Lives and Letters of Jessie and Annie McQueen reveals a really complex social history in the valley. It was possible to be a cowboy at one of the ranches and also to participate in sacred ceremonies. Chief John Chilihitsa was a prominent Indigenous horse breeder whose animals were sought-after for cavalry and infantry during WW1.Many families married back and forth into both cultures, were both cultures.

Margaret’s life was held in this balance and for me it was a way to honour two strands of valley history as well as to learn more myself about the Indigenous presence and culture(s).

5. Art in many forms is vital to this story, from Grandmother Jackson's baskets, to Emma Albani's singing, to Margaret's own photography. What role does this instinct for art and creativity play in women's lives, both in your fiction and more widely, in your opinion?

I think in a class-conscious society, the women who were encouraged to participate in the arts were often those with money and privilege. But for others, they found ways to make the practical things they did daily, of necessity, a way to explore creativity. Margaret sort of straddled two cultures and had opportunities that were perhaps not available to others. But I imagine other young women in her community – the Indigenous ones as well as the settlers – finding ways to do what they could. The Interior Salish baskets are often works of art – their forms, their imbrication. Yet they were made to be used, beauty yoked to function. Like quilts. An aside: I once went to a quilt show at Kilkenny Castle in Ireland, featuring 19th century quilts. Most of them were made by Anglo-Irish women from the upper class. The quilts were gorgeous – stars and elaborate designs made with silks, velvets, and taffetas. But I lost my heart to a rough well-used log-cabin patchwork made of scraps of sugar sacks, ticking, and what seemed to be pyjama fabric. Each square was lop-sided and the piecework was clumsy but I thought how much pleasure the quilt’s maker had probably taken in her work. That maybe she’d even been a servant in a house with beautiful quilts and she was inspired to try one of her own. In a way it was a subversive act. No one can fault you for sewing and piecing if you’re using scraps and rags and if the project has practical intent. She might have known that it would have lasting plain beauty as well.

My older son worked for a few years at the History Museum in Gatineau (he’s a historian and was hired to develop exhibits for the 150th anniversary of Confederation) and when we visited while he was there, he arranged for me to have a tour of the textiles collection. What an amazing wealth of (mostly) women’s work! Hooked rugs, Red Cross quilts created for displaced people in WW2, clothing, flags and banners, the most beautiful and astonishing material archive. I think I draw on that tour and subsequent visits to the curatorial wing of the Museum in more ways than I know.

In my writing, I sometimes let my characters do things I can’t even begin to do myself. They’re painters sometimes (Winter Wren and my work-in-progress) or singers (one character in The Age of Water Lilies) or curators (Anna in Sisters of Grass). It’s a chance to live vicariously...

5. As someone who is involved in sewing and needlework yourself, do you see a connection between the making involved in textiles and in writing? Do they inform one another for you? If so, how?

I’ve always said (and I believe it’s true for me) that I don’t see a hierarchy in my own creative pursuits, that they feel like part of living an integrated life. Sewing, writing, gardening, simple book designing (I run a small micro-press with a publishing partner, Anik See, showcasing literary novellas) – they are all very satisfying. I’m better at some of these things than others but I still find myself drawn to one or another for reasons I don’t always understand. Sometimes when I’m stuck with something in a writing project, I pick up a quilt; I’ll often find that the meditative work of sewing allows me to untangle issues in my writing.

Recently someone asked me when I began to write seriously and I guess I was in my early 20s but as far back as I can remember, I felt compelled to write things down. I’d feel such an urgency to make stories of things I loved and wanted to remember, though I’d often not complete them because I didn’t have the vocabulary I knew even then I needed to make the thing true. Didn’t know to progress beyond the initial description. And I also felt a similar urgency to make things with my hands, out of wood or fabric, even though I came from a family without any interest in such things, so there wasn’t much encouragement. It wasn’t until much later that I saw how I could put that urgency and interest to good use and with the guidance of a couple of really good teachers, in high school and at university, I learned to take myself and this work more seriously.

6. I know that like the readers in the Literary Sewing Circle, you are also a sewist and stitcher, with a wide range of interests. What are some of your favourite creations, and where can people find out more about your creative pursuits?

I’ve always sewn in a practical way – curtains, mending, basic clothing (though I wasn’t very good at that; too careless...). I began quilting about 35 years ago after sorting some fabric and suddenly seeing harmonies in several of the pieces. I cut out squares in a sort of heat of inspiration, though most of them were a bit lopsided, and sewed them together in courses, figuring things out as I went along. I can’t say the result was beautiful, though one of my sons requested that I leave it to him in my will—my response was to make a few simple repairs and give it to him then-- but I learned so much and it ignited a passion which has endured to this day. I love the process even more than the finished result. I have a big wicker rocking chair in the kitchen by our woodstove and I keep a quilting basket near so that any time I have a little time, I sit and quilt. It’s very meditative for me—the feeling of the fabric under my hands, the way quilting itself creates texture. I almost always have two quilts in progress at once so that I can switch to keep things interesting.

About 20 years ago I began to do some indigo dye work too, trying out various shibori techniques and discovered the extraordinary Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada’s book on shibori: “When the cloth is returned to its two-dimensional form, the design that emerges is the result of the three-dimensional shape, the type of resist, and the amount of pressure exerted by the thread or clamp that secured the piece during the cloth’s exposure to the dye. The cloth sensitively records both the shape and the pressure; it is the “memory” of the shape that remains imprinted in the cloth. This is the essence of shibori.” I think quilting in general and the craft of shibori specifically is about memory, how we imagine our work before and as we do it, how design can be a metaphor for containing unruly thinking, how our lives are somehow embedded in what we do. My quilts are often a way of figuring out a difficult issue or a solace during times of sorrow or a means to explore colour, texture, and the nature of love. They extend my interests in geography and mapping, in salmon cycles, working out representative geometry for house-building, and I’m always thinking of ways to add something new to the process.

I’ve written about quilting and indigo dye work, most recently in Blue Portugal & Other Essays, published in the spring of 2022 by the University of Alberta Press. There are essays about quilting in earlier books too – Phantom Limb, Red Laredo Boots, and Euclid’s Orchard. The title essay in Euclid’s Orchard is about the creation and abandonment of an orchard, mathematics, coyote song, and quilting as a way to communicate with my younger son whose personal trajectory took him far from home. (I made him a quilt based on the essay and describe the making of it in the piece.) My novella Patrin is in part about a quilt that is also a map, a map of a family’s history. I also write about quilting from time to time on my blog.

7. Are you working on anything else that you'd like to share right now?

I have a long essay forthcoming in Sharp Notions: Essays on the Stitching Life about working on quilts as I helped my husband recover from bilateral hip replacement surgery in 2020. During his surgery, which was successful, he sustained a compression injury to his sciatic-peroneal nerve which resulted in a paralyzed foot. It was a difficult time for both of us; it was during the first year of the pandemic; we were advised to consider him immunocompromised, so we couldn’t ask others for help, apart from health professionals; and while he healed, I sewed, and we both worked together on his therapy. There were many correlations between the seams I was making and the (partial) regeneration of his peroneal nerve. The story has a mostly happy ending in that he’s made a pretty good recovery, has about 80% use of the damaged foot, and we learned things about ourselves and our capacity for figuring out how to face difficult things. I’m also working on a novel set in a small fishing village, based on my own community, and there are quilters in it, knitters, and an artist who uses both paint and textiles to bring her dreams to life.

*************************

Thank you for sharing some of your writing and sewing journeys with us, Theresa! It all sounds so thoughtful, and I can't wait to read your upcoming work. We hope you'll enjoy seeing the projects we make inspired by your writing.

You can find out more about Theresa here:

Website

Twitter